IBC clients - reimagined

IBC was designed from the start to be an open, permissionless and trust-minimized interoperability protocol. These requirements led to the design of the (light) client based approach, specified in the 02-client specification.

As the IBC protocol originated within the Cosmos ecosystem for chains with Tendermint consensus, the most common IBC client is the tendermint client. The IBC connections built on top of the Tendermint IBC clients used in the early phases of (production) IBC, are based on remote consensus proof verification on the host chain (i.e. the chain that runs the light client). Thus, in this case the security of IBC reduces to the security of the connecting chains and the connection is trust-minimized.

Many in the IBC community have thus started to consider the IBC protocol as synonymous with consensus proof based light clients. Recently however this is changing, in part due to the work Polymer is doing.

A short and succinct summary of an IBC client's functionality is the following: a light client stores a trusted view of the remote chain or "consensus state", and provides functionality to verify updates to the consensus state or verify packet commitments against the trusted root.

As you can see, we need a trusted initial view of the remote chain and a way to verify updates. The way this verification is done, is an implementation detail. This understanding opens up the design space for IBC clients.

We'll give a short overview of the different verification methods that can also be implemented by an IBC client, but first let's take a look at a more basic client diversity.

IBC clients for heterogeneous chains

Even though IBC was originated as part of the Cosmos vision of a network of interoperable L1s, mostly built using Tendermint consensus and Cosmos SDK, the team responsible for designing the specification took no shortcuts and built the protocol for a heterogenous network of many different chains with different consensus types, existing and future ones.

To ensure maximal compatibility, the requirements on hosts chains to implement IBC were intentionally kept minimal.

As such, for each chain with a different type of consensus, there will be a different client type which will define rules for the client to verify according to the protocol of said consensus type.

Initially, IBC adoption outside of Cosmos SDK chains (with Tendermint consensus) has been rather slow, but this is picking up. For example, there is the GRANDPA client developed for chains from the Polkadot ecosystem.

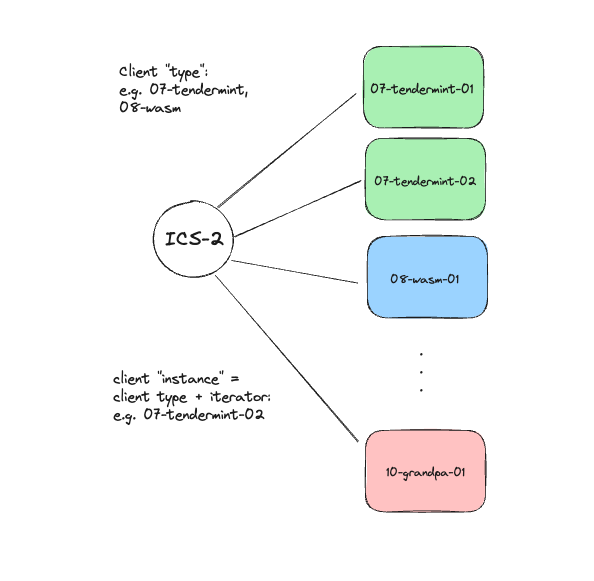

Client type vs client instance

It's important to realize the difference between client types and client instance, i.e. an instance of said type. This implies that there are only a few different client types corresponding to chains with different consensus protocol. For each instance an monotonously increasing sequence number is assigned to identify different instances.

Client are then denominated as follows : <ICS spec number>-<name string>-<iterator>. For example: 07-tendermint-123 for Tendermint chains or 10-grandpa-345 for a Polkadot/Substrate chain.

IBC clients: beyond consensus proof verification

The separation of the transport layer and the state layer is an important towards a unified transport standard while allowing flexibility in terms of state verification. The IBC client definition is loose enough to allow for verification beyond consensus proofs to update its view of the remote chain. Multi-signature, single signature, threshold signatures and more can all be considered valid clients. Any of the trust mechanisms listed below can be represented as an IBC client.

This implies that many of the existing bridges or other interoperability solutions of today, mostly limited to state layers concerns, could be IBC clients in the future.

We list an overview of the different ways to bridge at the moment.

Centralized bridges

These are also known as proof of authority (PoA) bridges and are a fixed group of private keys that have the authority to attest to bridged state from one chain to another. When there’s no open participation model, the bridge can only be considered to be centralized.

The obvious downsides of this approach is that the private keys used in the signing process are prime targets for hacks.

Centralized bridges can migrate to a multi-signature bridge by allowing for open participation for signers.

Multi-signature bridges

Multi-signature bridges can be a proof of stake (PoS) validator network or a decentralized oracle network. The key takeaway is that there is some dynamic group of signers that can change over time. There is usually some economic value that’s staked and can be slashed upon misbehavior to guarantee the security of the bridge.

The downside of centralized bridges still applies here but the attack vector now also comes in the form of economic attacks to gain control of the bridge.

Additionally, a major issue with relying on a few observers of a chain to attest to state is that the local view of the observers is likely not consistent with the view of a chain with a large validator set such as Ethereum. This is true for both centralized and multi-signature bridges.

The IBC solomachine client is a client that allows a single machine with a public key (can be a single public key or a multi-signature public key) to implement the unified IBC client interface to use the IBC transport layer.

Centralized or multisig bridges could run an IBC solomachine client to interact with the IBC network (potentially in anticipation of upgrading to higher levels of security and trust-minimization).

Light client bridges

Light client bridges rely on the verification of a consensus proof generated by a chain. Each counterparty chain verifies the consensus proof of the other to establish a state layer connection.

Light client bridges are more secure than centralized and multi-signature bridges but are more expensive to verify.

Since clients are verifying the consensus of a chain but not the execution, this approach has an honest majority assumption security wise.

At the time of writing, most IBC clients still adopt the light client with consensus proofs model. So is the tendermint client in ibc-go.

Optimistic bridges

-

Optimistic bridging in its strongest form involves the destination chain being able to verify fraud/fault proofs produced by the source chain. This is execution verification instead of consensus verification. The client would accept new headers optimistically and update the ConsensusState, with the ability to submit fraud or fault proofs by a challenger within a fraud window.

-

There’s also a weaker form of optimistic bridging that involves a sharded economic security model that relies on a relayer staking a slashable bond on the source chain although this presents a significant security reduction.

Optimistic bridges generally have good security that increases with the fraud proof window. The amount of capital and resources an attacker would need to spend to censor a fraud proof increases with the size of the fraud proof window.

An optimistic bridging model implies an honest minority assumption or a 1-of-N assumption security wise.

ZK bridges

-

Zero knowledge (ZK) bridging in its strongest form involves the destination chain being able to verify execution proofs produced by the source chain.

This type of ZK bridging with validity proofs implies execution verification, instead of consensus verification.

-

The most common form of zero knowledge bridging in interoperability is converting consensus proofs into zero knowledge consensus proofs. Using zk consensus proofs is as good as light client bridges with respect to security but weaker than optimistic bridges.

This type of ZK bridging model implies an honest majority assumption, as is the case if the consensus proofs were regular and not ZKP based.

The above Optimistic and ZK clients might sound very analogous to the verification mechanism used in rollups. Indeed, a rollup essentially is a view into another chain (the rollup) from its settlement layer and thus the same range of proving methods can be utilized.

Canonical bridges

Canonical bridges are run by the team building an L1 or L2 and sanctioned by the team to move liquidity in and out of their ecosystem.

They theoretically can be any of the above in a fully decentralized setting.

However, many canonical bridge implementations are highly centralized. They generally consist of some centralized set of private keys that are authorized to bridge state from one chain to the next.

In the long term, we may see canonical bridges start moving over to more secure forms of state layer bridging.

Even more diversity...

Extending the IBC clients to allow for verification beyond consensus proofs is one element to make clients more diverse. There is another element we still need to consider though, the modular paradigm. Read on in the next section to find out how IBC can work in the modular world.